- Executive Resilience Insider

- Posts

- Why your best plans always fail

Why your best plans always fail

MIT research: the more sophisticated your planning, the worse your execution. 5 frameworks that flip the script in 90 days.

Donald Kieffer walked into Intermatic as the new senior vice president of operations and saw disaster. On-time shipments sat below 60%. The industrial manufacturer had strategic plans, formal processes, annual budgets. What they didn't have was anyone looking at why shipments actually failed.

That first morning, Kieffer did something unusual. He pulled his executive team together and told them: get involved with operational details immediately. Not to analyze. Not to plan. To understand and fix.

Four months later, on-time shipments exceeded 90%—a level Intermatic had never achieved.

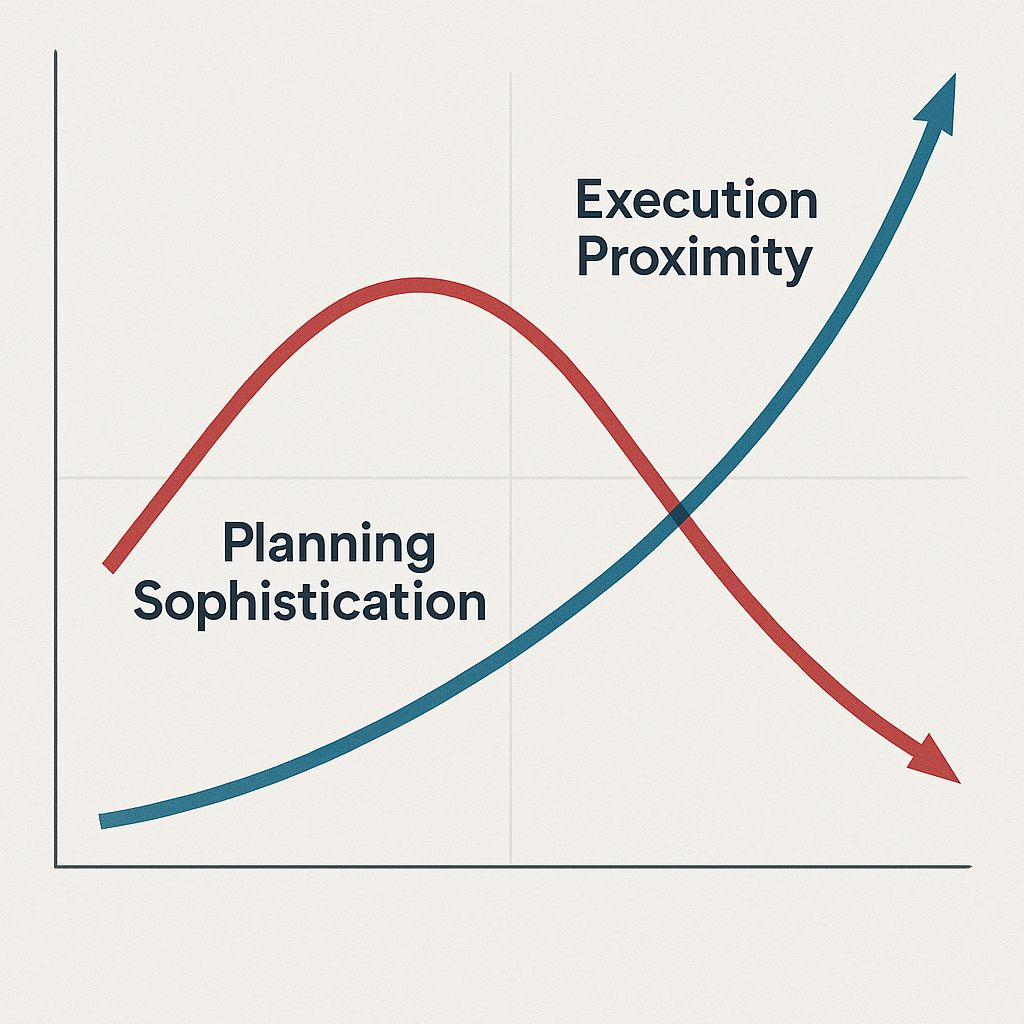

MIT Sloan professors Nelson Repenning and Donald Kieffer spent decades studying why some leaders consistently outexecute others. The answer challenges everything taught in business school: the more sophisticated your planning, the worse your execution. Leaders who engage directly with frontline work systematically crush those managing through hierarchies and formal frameworks.

The paradox appears everywhere:

Annual planning sophistication ↑ = Execution speed ↓

Executive distance from operations ↑ = Organizational chaos ↑

Big initiative focus ↑ = Small problem accumulation ↑

Fortune 500 executives invest millions in planning cycles while competitors capture markets through something cheaper and faster: showing up on the factory floor. The gap isn't marginal—it's multiplicative. You have 90 days to build hands-on intelligence before competitors establish advantages that planning documents cannot replicate.

72% of executives can't name their own priorities

Harvard Business Review researchers Kaplan and Norton tracked hundreds of companies and found something disturbing: 67-90% of strategies fail execution. Not because the strategies are wrong. Because the plans never survive contact with operational reality.

The numbers get worse. Gallup pegs the annual cost of disengagement and organizational chaos at $438 billion globally—with broader estimates reaching $8.8 trillion, roughly 9% of world GDP. Employees spend 60% of their time on "work about work" rather than actual value delivery. Workers get interrupted every three minutes and need 23 minutes to refocus.

Meanwhile, 72% of executives responsible for executing strategy cannot list their organization's top three priorities. Less than 5% of employees understand company strategy. Leadership teams spend months developing plans they then discuss for under one hour monthly.

Back at Intermatic, Kieffer's team discovered why the plans failed. By midafternoon of that first day, problems surfaced everywhere. Inventory locations wrong. Paperwork incomplete. Packaging issues. Customs delays. Transportation breakdowns.

Instead of scheduling meetings to discuss findings, the team started solving problems on the spot. They called suppliers directly. Fixed paperwork errors immediately. Addressed packaging constraints in real-time.

The dysfunction Repenning and Kieffer identify runs deeper than poor execution. Executives assume annual plans, complex budgets, and formal frameworks can capture operational reality. They cannot. Markets shift. Supply chains disrupt. Client needs evolve. Workers facing these realities have no choice but creating private workarounds—undocumented solutions that solve immediate problems without building organizational capability.

"When circumstances inevitably change, workers who are motivated to get the job done have little choice but to find their own way to do things differently. The workarounds are private, and there's no way for others to benefit," Repenning explains. Organizations enter firefighting mode, bringing teams into evening and weekend emergency sessions that better work design makes unnecessary.

Shipment metrics at Intermatic began improving within days. The chaos disappeared. Staff energy shifted from firefighting to strategic issues. Eventually, frontline supervisors told Kieffer something remarkable: his attendance at daily meetings was no longer necessary. Staff could run operations themselves.

"Stay close to day-to-day work, help employees solve problems that get in the way, and don't sit back and blame someone else for dropping the ball," Kieffer explains. "Go find the issue and help to resolve it. Don't underestimate the impact of solving small, important problems every day."

Markets don't care about your annual plan. They reward whoever executes fastest.

5 frameworks that convert corner office strategy into factory floor results

Framework 1: The Problem Proximity Accelerator

Executives love big initiatives. Corner offices. Big budgets. Transformation projects. Yet Repenning and Kieffer's research proves smaller fixes "become the engine driving larger ongoing transformation."

Palace Station Hotel discovered front-desk staff missed email capture goals not from lack of skill but operational overload. Employees had to communicate restaurant deals, shuttle schedules, betting regulations—email requests got lost in the noise. Rather than new training or incentive programs, leadership and staff developed simple checklists. Email capture rates jumped immediately.

Women's Lunch Place in Boston served women experiencing poverty and homelessness. Every visitor went to experienced counselors, creating bottlenecks. Front-desk staff started asking upfront questions: could they solve straightforward problems directly, like obtaining subsidized subway passes? This shift let the organization serve more women, document improvements, and secure additional funding.

The critical insight: start with problems having simple solutions and immediate results. Large organizational changes create rocky transitions. Learning curves disrupt operations before improvements materialize. Beginning with easily solvable problems minimizes disruption while establishing problem-solving patterns that spread organically.

"You're a leader with big responsibilities and a big office. You think you need to do big things," Repenning observes. "But organizational change is retail and not a wholesale activity."

Organizations successfully enhancing execution capacity through systematic small improvements increase profitability by 77%. Not through strategic initiative sophistication. Through daily problem resolution.

Framework 2: The Discovery Structure Builder

Palace Station Hotel leadership thought they understood why front-desk staff missed email capture goals. They were wrong.

When executives actually engaged with floor reality, they discovered employees faced operational overload invisible from the corner office. Staff had to communicate restaurant deals, shuttle schedules, betting regulations—all while checking guests in. Email requests got lost in the noise. The solution emerged from shared discovery: leadership and frontline staff jointly defining what activities delivered targets and what actually worked versus what looked good in theory.

BP refinery faced a similar revelation. One-third of purchase orders required rework, delaying them for days. The procurement software couldn't capture dozens of steps necessary to request, order, and pay for parts. Refinery operators rarely sat at computers, making information gathering nearly impossible.

The answer wasn't redesigning systems or implementing new software. BP determined which details most often went missing from purchase orders, then asked requesters to email those specifics with each request. Orders requiring rework dropped below 10%.

This requires leaving corner offices and visiting loading docks, factory floors, finance departments. Not ceremonial visits. Problem-solving engagement.

"The 'attaboys' from the CEO don't add a lot of value, and the ceremonial visits don't teach a lot," Repenning notes. "If you carve out time to solve little problems, the example you set is powerful and spreads like wildfire through the organization."

When executives demonstrate hands-on problem-solving, expectations become clear through actions, not PowerPoint presentations. Organizational culture shifts from blame assignment to problem resolution.

Framework 3: The Flow Regulation System

Yale University Hospital cut wait times 20% and reduced per-case costs 19%. Not through new technology. Not through staff training. Through one simple change: they linked daily surgeries to exact intensive care unit beds available for postoperative patients.

The insight seems obvious in retrospect. Maximizing surgery numbers based on surgeon availability meant completed surgeries with no recovery beds available. Patients waited. Staff scrambled. Costs ballooned.

Conventional wisdom says pressure creates performance. Operational reality reveals overloaded systems grind to halt at the smallest disruption, like stalled cars on rush hour highways.

Many organizations respond to overload by expediting high-priority items. This leaves partially completed projects accumulating—work started but never finished because new urgent priorities constantly arrive. The backlog grows. Teams scramble. Quality suffers. Everyone works harder while accomplishing less.

Regulating for flow means closing the airplane door before takeoff: once work starts, it moves to completion. More work enters only when downstream capacity exists. This requires matching work intake to actual system capacity rather than aspirational targets that look good in quarterly reviews.

The framework challenges pressure-creates-performance assumptions. Research demonstrates overloaded systems produce worse outcomes than capacity-regulated ones. Organizations must resist expediting temptations that create partial work inventory throughout systems while nothing actually finishes.

Framework 4: The Human Chain Connector

"I'd bet many organizations use emails and meetings almost exactly backwards," Repenning observes. Meetings become 55-minute slide presentations. Email threads require numerous replies working through complex issues that need real dialogue.

Human interactions drive most workflows. Simple connection protocols consistently outperform complex software and automated processes.

BP's procurement challenges proved this. One-third of purchase orders required rework, delaying them for days. The problem wasn't inadequate software—dozens of steps required for parts ordering broke down when refinery operators couldn't easily provide necessary details. The software existed. The processes existed. What didn't exist was clear human connection enabling smooth information transfer.

Two simple fixes solved it: email handoffs and huddles.

Email handoffs work when everyone agrees on transferred information. BP established clear expectations about required details for purchase requests, dramatically reducing rework. No new software. No process redesign. Just clarity about what information moves from person to person.

Huddles address situations requiring conversation before proceeding. BP used brief, focused gatherings for nonstandard purchase requests because short conversations worked better than ambiguous email threads. The gatherings stayed brief and action-oriented—like sports huddles determining next plays.

Map actual information flow through your systems, then design connection points enabling smooth transfers. This beats designing ideal processes that look perfect in flowcharts but collapse on contact with reality.

Framework 5: The Work Visualization Protocol

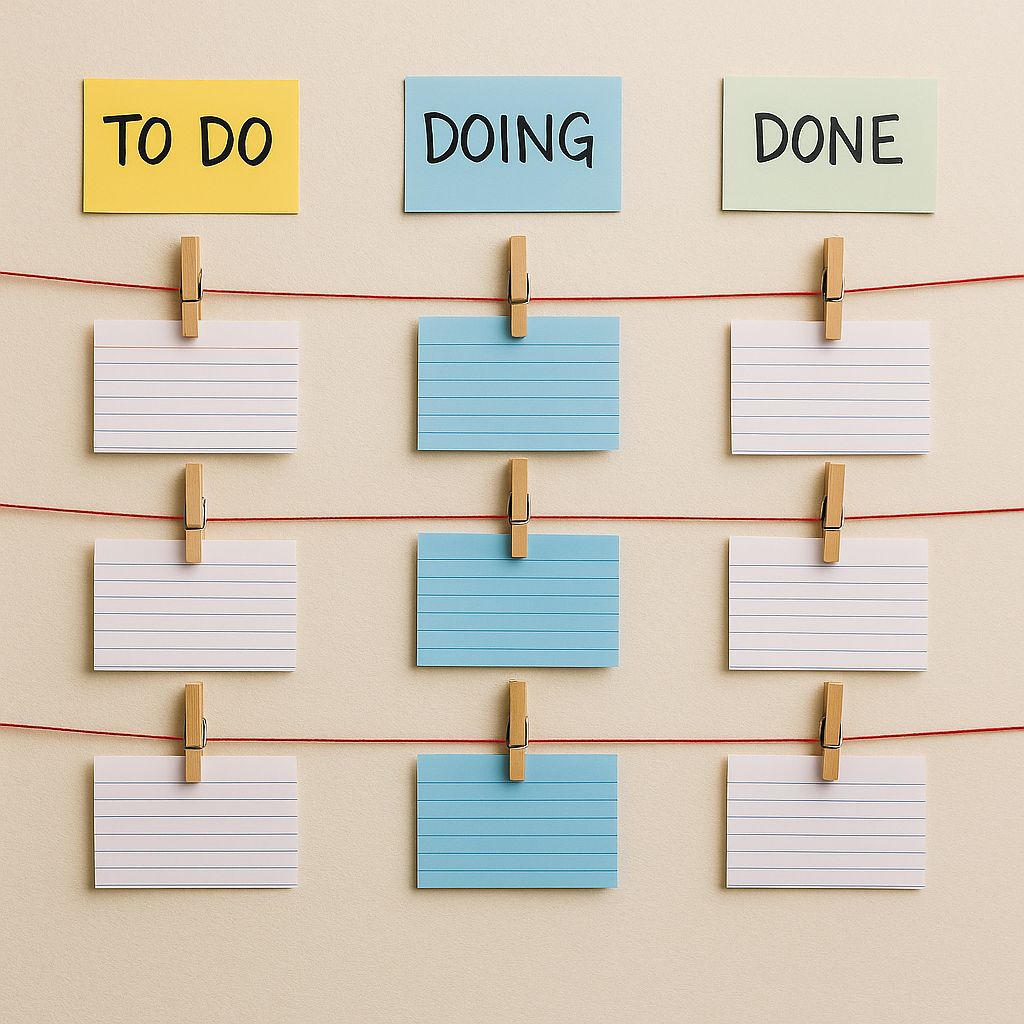

Index cards, clothespins, and string. That's what Fannie Mae used to cut monthly book-closing time from 13 days to six days.

They documented required data, necessary handoffs, and tasks, then held daily huddles in front of physical flowcharts. No enterprise software. No digital transformation initiative. Just making invisible work visible.

This physical visualization served purposes sophisticated tools often miss. Teams could see work progression. Bottlenecks became obvious. Dependencies clarified. Everyone understood system state without status meetings or email updates. Questions got answered in seconds rather than days.

Digital tools become necessary for global organizations—they help illustrate where work needs completion and enable resource allocation across locations. However, Repenning cautions against overreliance: "The magic is the quality of the conversation a physical board drives. That's good for making decisions and solving problems."

The framework works because it makes invisible work visible. Assumptions about workflow often miss operational realities—the handoffs that fail, the dependencies that block progress, the bottlenecks that accumulate. Physical or digital visualization exposes actual process execution, enabling continuous improvement through direct observation rather than theoretical modeling.

Work happens in the shadows until you force it into the light. Visualization drags operational reality into view where teams can see, discuss, and systematically improve it.

The 90-day proximity window

Remember Kieffer walking into Intermatic's chaos? That wasn't his first transformation. Years earlier at Harley-Davidson's Twin Cam 88 engine plant, he'd learned the same lesson: sustainable change requires continuous problem-solving rather than annual planning cycles.

The pattern repeated at Intermatic. It repeats everywhere leaders try it.

The performance gap isn't subtle. Intermatic: 60% to 90%+ on-time shipments in four months. Yale Hospital: 19% cost reduction through capacity-based work design. Fannie Mae: 54% faster book-closing through index cards and string. Corporación Industrial: 5X return on small operational improvements.

Compare this to the 67-90% of strategies that fail execution despite massive planning investments.

Market leaders are discovering hands-on execution while establishing competitive positioning that corner office planning cannot replicate. Companies implementing these frameworks within 90 days establish advantages that planning-optimized executives cannot match.

Kieffer's frontline supervisors eventually told him his attendance at daily meetings was unnecessary. Staff could run operations themselves. That's the real victory—not heroic executive intervention, but building systems where problems get solved before they compound.

You face a choice. Continue investing in frameworks that fail 67-90% of the time. Or do what Kieffer did: walk onto the floor and start fixing things.