- Executive Resilience Insider

- Posts

- How Leadership Bottlenecks Cause Burnout

How Leadership Bottlenecks Cause Burnout

When your best performer wants to quit, it’s rarely about workload—it’s about your leadership design.

Lauren Dreyer's top performer walked into their one-on-one with news that stopped her cold.

"She told me she was looking for another role because she loved the work, she loved our relationship, but she couldn't handle the burnout anymore," says Dreyer, who leads strategic initiatives at Fidelity. "That was such a wake-up call for me."

This wasn't about difficult stakeholders or unrealistic deadlines. The work itself energized this team member. The relationship was strong. But the pace was unsustainable, and despite weekly check-ins where Dreyer asked "What can I do to help?"—nothing changed.

The problem wasn't visible until it nearly cost Dreyer her best person. She was the bottleneck. Every commitment flowed through her. She attended executive meetings, made decisions about what the team would deliver, then returned to info-dump direction and let them organize around it.

"I hadn't embraced the mindset of empowering the team to tell me what was doable and what was possible," Dreyer explains. "I wasn't giving her the space to figure out trade-offs. I was just giving her one more task that she would say 'I don't even know where to start.'"

What happened next transformed everything. Dreyer stopped making decisions for her team and taught them to think like owners. Productivity increased 60%. The planning-to-execution ratio flipped from 80:20 to 20:80. They could pivot weekly without frustration.

"It's a way for a leader to leverage themselves by teaching team members to think as if they are the leader of the team."

Here's what most leaders miss about leverage:

Leaders who make decisions for teams work 80% on overhead, 20% on execution. Leaders who teach teams to decide flip this ratio entirely.

Asking "what do you need?" without sharing context creates dependency—teams can't propose solutions without seeing the full picture leaders see.

The bottleneck isn't workload—it's leaders who won't share the information that enables teams to make owner-level trade-offs.

Shifting from manager to mentor frees 40-50% of leader time for strategic work instead of daily firefighting.

The Leadership Leverage Reality:

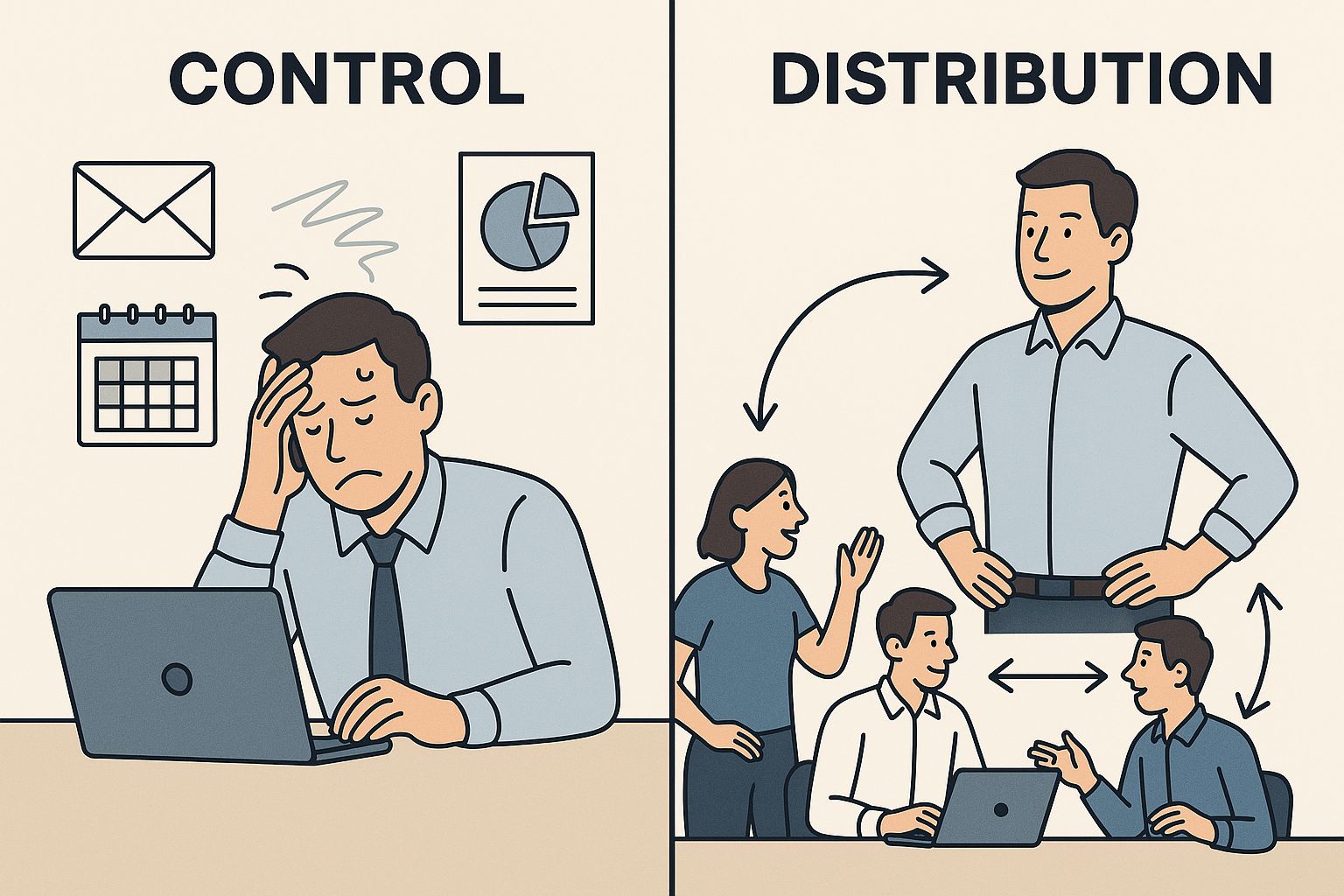

Control scales to your personal bandwidth. Distribution scales to your team's collective capacity. The choice determines whether you multiply impact or hit permanent capacity limits.

Why control-focused leadership creates burnout

Dreyer had inherited teams using Agile—sprints, iterative work, small increments. The tools were there. But she hadn't changed how she led.

"I really saw that as something the team did, and I was still operating in a traditional manner," she says. "I would go to meetings with senior executives giving us direction, make commitments on behalf of the team, then come back and info dump what I had heard and what we needed to deliver."

Her team spent 80% of their time on planning and overhead, 20% on actual work delivery.

When her top performer nearly quit, Dreyer realized the pattern. She kept asking "what can I do?" but never gave her team the authority to answer honestly. She wasn't creating space for them to say "this timeline isn't realistic" or "if we commit to this, we need to deprioritize that."

"It always felt like it was about the workload and the demands coming at us. I didn't make the connection to what I was doing."

The shift started when Dreyer gave her team the information she could see—business priorities in rank order, strategic context, actual constraints—and trusted them to determine what was doable.

"They would have a better approach than I would've had to planning," she discovered. "They would provide me the information and transparency back by breaking down the work and helping me go back to leadership teams to negotiate a deadline or request more resources."

The team could surface trade-offs Dreyer never saw. They could propose alternatives she wouldn't have considered. Because they understood execution details she didn't.

But the transformation took patience. "Months of iteration where there's back and forth: 'Do you really trust us to decide how we approach this?' 'Yes, I really do trust you.'"

One team member had spent 30 years being told what to do. "It's uncomfortable for me that you're asking me what I wanna do or how I wanna do it," he told Dreyer.

Another kept saying yes to projects, then driving herself crazy trying to deliver perfection. "It took three or four weeks to have this person be comfortable sharing that's what they were doing," Dreyer recalls. "I had to help them understand: 'I'm not giving you a project to deliver with perfection. Let's define what step one looks like.'"

The leverage multiplication comes from teaching teams these new ways of thinking. But it requires leaders to genuinely believe in distribution, not just implement new processes.

Three distribution systems that multiply leadership impact

Framework 1: The Context Distribution System

From Decision Bottleneck to Information Provider

The fundamental shift: stop making decisions for your team, start sharing the context that lets them make owner-level decisions themselves.

Dreyer's breakthrough came when she realized she could give her team the same information she had. Not just "here's what we need to do" but "here are our top 5 business priorities in order, here's why that ranking exists, here are our constraints, here's what leadership is concerned about."

Then she asked: "Given this context, how would you approach our current work? What would you prioritize?"

Initially, her team looked to her for answers. She had to resist giving them. "What's your thinking? If you were in my seat, what would you decide?"

This taught ownership thinking. And it revealed something powerful: teams often made better decisions than she would have because they saw execution details she didn't.

"You have to break down ideas like 'this is my swim lane, that's your territory,'" Dreyer explains. "Really get the team thinking about the team as a whole and what does it look like if all of the work is being presented to us, and it's up to you, all of you, to raise your hand for what you're going to do."

But context distribution requires killing the culture of always saying yes. "No one ever asked me, 'Do you have capacity for this?'" Dreyer says. "The work comes at you like a fire hose and you just figure it out."

She had to make capacity discussions routine and judgment-free. Not "why can't you handle this?" but "given your current work, when could you realistically deliver this?"

When Dreyer had team members who couldn't answer "what do you need?" she realized they'd never been asked to think that way. "I can't read your mind. Please, let's be transparent about whether you're over-utilized or under-utilized, what you feel comfortable with versus where you need help."

The transparency works both ways. Teams learn to articulate capacity and needs. Leaders learn what's actually happening at execution level. This shared understanding enables realistic planning instead of optimistic commitments followed by burnout.

What to do:

Create weekly context sessions (30-45 minutes). Share top 3-5 business priorities ranked with explanation, current constraints (budget, timeline, resources), and recent leadership concerns. Then ask the team: "How would you approach this? What trade-offs would you make?" When they look to you for answers, redirect: "What do you think?"

Establish capacity transparency as routine practice. In planning sessions, ask each person: "What percentage of capacity do you have available?" Require numeric estimates. When new work arrives, ask the team: "Who has capacity? What would we need to deprioritize to take this on?"

Track when team recommendations differ from what you would have decided. Document outcomes. You'll find their approach often worked better because they saw details you missed.

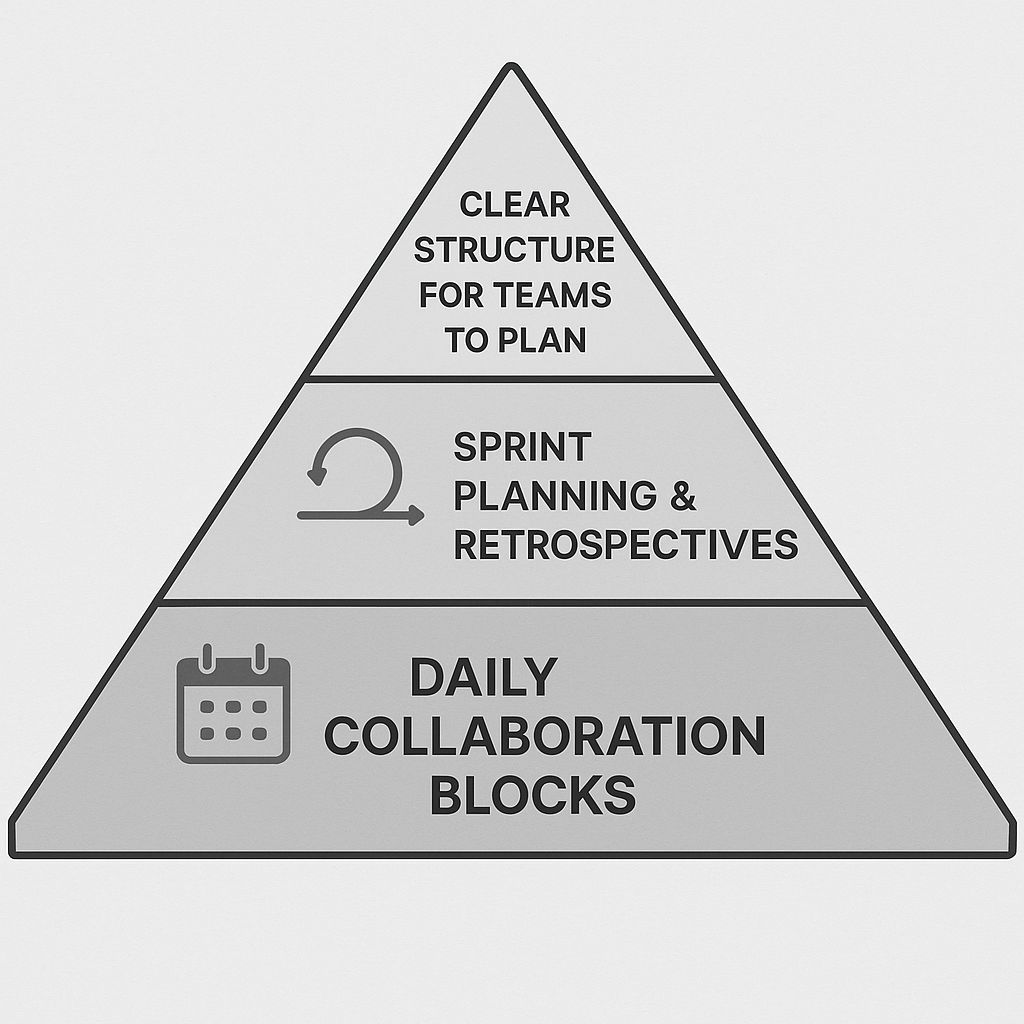

Framework 2: The Planning Architecture System

Structure Time That Enables Ownership

Distributed decision-making requires structured collaboration, not ad-hoc meetings that never find calendar space.

Dreyer's team needed high-level partnership to do their work effectively. Ad-hoc scheduling wasn't working. "We couldn't get the time, there was always too much information to share."

The solution felt counterintuitive: daily hour-long collaboration sessions. "The team plans ahead of time whether that will be for a working session, decisions needed, feedback. We cancel it if we don't need it. Because of that, everyone is able to produce at a much higher rate because they know if I need it, I have time tomorrow."

This eliminated constant interruptions of "can we find time to discuss this?" The standing time block meant teams could address blockers within 24 hours instead of waiting days for scheduling.

The team also uses sprint planning where they write their own stories and plan their own work in advance. "They will amaze you with what they come up with, with the barriers they can foresee, with the challenges you didn't think about."

Context matters. Structured time for teams to work through problems together generates insights that scattered meetings never produce.

The planning isn't overhead—it's investment. Upfront planning time pays back in execution efficiency because teams identify blockers before hitting them and plan realistic timelines based on actual capacity.

Dreyer's team went from 80% time on planning overhead to 20%. The flip happened because better planning reduced fire-fighting and rework. When teams understand context and plan realistically, execution accelerates dramatically.

What to do:

Establish daily collaboration blocks (45-60 minutes) at consistent times. Have teams pre-plan agenda based on their needs—working sessions, decisions, feedback, blocker removal. Cancel when not needed but maintain the time block so it's always available.

Implement sprint planning appropriate to your team's work (1-4 weeks). Before planning sessions, have team members document: work they're taking on, estimated effort, dependencies, potential blockers. In planning, review as a team: Does this reflect our capacity? What could go wrong? What trade-offs are we making?

After each sprint, run retrospectives: What went as planned? What surprised us? What will we do differently? This builds muscle for realistic planning.

Track your planning-to-execution ratio. Initially you may be 60:40 or 70:30. Target moving toward 20:80 over 6-12 months as planning improves and fire-fighting decreases.

Framework 3: The Leader Role Transformation

From Manager to Developer of Leaders

The ultimate leverage multiplication happens when leaders shift from managing work to developing people who can manage work themselves.

Dreyer's time allocation transformed completely. "Prior to working this way, I focused on what was expected of me and my team and how would we deliver that work. Now I focus on how am I developing future leaders?"

Her direct time became coaching by request. "I feel more like a mentor than a manager or boss. I'm getting more interesting questions: 'Here's something tricky about the environment and stakeholders we're working with. How would you approach that? Here's what I was thinking.'"

On her own time, she could finally do strategic work: "Where is the business going? How can I make sure I'm seeking out the information and partnerships that the team needs to be better?"

This freed 40-50% of her time from daily decision-making and firefighting. But it required explicit changes in how team members were evaluated.

"I had to be very proactive about how they were going to be evaluated and what was going to be important—not just the work output and definitely not who's in the spotlight, but how are we getting the work done and are you empowering the team?"

The transformation created teams capable of operating without her. "If I go on vacation, anyone can contact any member of my team and they will know how to at least engage their peers to figure out how to get something done."

This isn't delegation—it's genuine distribution. Team members think like owners because they have the context, authority, and structure to make owner-level decisions.

The 60% productivity increase came from this shift. Teams planning their own work with full context produced better outcomes than when Dreyer planned for them. And she gained capacity to do work only leaders can do: spotting opportunities, solving systemic problems, developing talent.

"I'm so proud of my team every single day," Dreyer says. "They inspire me. It's amazing to see how they grow and work together, and also how much it's unlocked my potential as a leader."

What to do:

Redefine your role explicitly: "My job is to give you context, clear blockers, and develop your leadership capabilities—not to make all decisions." Shift 1-on-1s from status updates to coaching: "What's a tricky situation you're navigating? How are you thinking about it?" When people ask you to decide, redirect: "What do you think we should do?"

Evaluate team members on empowerment: "Did you help teammates succeed? Did you surface trade-offs and propose solutions?" Track your time allocation—target 30-40% on coaching and development, 30-40% on strategic positioning, 20-30% on blocker removal. If you're spending over 30% on daily decisions, you haven't distributed authority.

Document examples where team decisions exceeded yours. Share these stories to reinforce their capability and your confidence in distribution.

Why distribution multiplies while control limits

The transformation isn't about working less—it's about working on different things. Dreyer still works hard, but on developing people and strategic positioning instead of making daily decisions.

The results prove the approach: 60% productivity increase, 80:20 overhead ratio reversed to 20:80, teams pivoting weekly without frustration, and leaders freed to do strategic work that creates long-term value.

But it requires genuine commitment. "Make sure you really believe that this is something you want to do to empower the team," Dreyer advises. "It goes way beyond these practices and processes."

Leaders who maintain control scale to personal capacity. Leaders who distribute authority scale to collective capability. The difference isn't incremental—it's multiplicative.